Steven Soderbergh gave me the best advice I’ve ever heard.

I met Mr. Soderbergh at the bar of the famous hotel Majestic during the Cannes film festival a couple years ago. Between sips of Jagermeister, I asked him if the rumors were true: Was he giving up filmmaking?

He confirmed it to be true: Mr. Soderbergh, the Oscar winner and posterchild of the nineties indie movement was finished. He was going to become a painter instead. I didn’t ask him why, but I told him I enjoyed the lesser appreciated Schizopolis as much as I enjoyed the film that made him famous.

He said, “I only knew one film executive when I wrote Sex, Lies, and Videotape. I got lucky. It was easier for me then than it will be now for you.”

I asked him if he had any advice?

“Yea. Don’t screw up. Or it's over. “

Let me back up for a moment.

I met Mr. Soderbergh at the bar of the famous hotel Majestic during the Cannes film festival a couple years ago. Between sips of Jagermeister, I asked him if the rumors were true: Was he giving up filmmaking?

He confirmed it to be true: Mr. Soderbergh, the Oscar winner and posterchild of the nineties indie movement was finished. He was going to become a painter instead. I didn’t ask him why, but I told him I enjoyed the lesser appreciated Schizopolis as much as I enjoyed the film that made him famous.

He said, “I only knew one film executive when I wrote Sex, Lies, and Videotape. I got lucky. It was easier for me then than it will be now for you.”

I asked him if he had any advice?

“Yea. Don’t screw up. Or it's over. “

Let me back up for a moment.

I was on my way out of Europe. 2 weeks remained in paradise, then I was shipping back to the United States after a decade living abroad. I’d lived throughout eastern Europe, and before that, in Italy, and had enough adventures, foul ups, near hits, many misses, and ramblings to fill three lifetimes. I was exhausted, fatigued by a life of constant extroversion, of constantly living six inches in front of me at a time, of constant adaptation, of surviving, of being a stranger in a strange land, and losing so much of myself in the process. Home was simultaneously everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

I was on my way back to my family for a wedding, and then anything could happen. Maybe I’d come back to Europe, maybe I’d move to LA, maybe I’d lock myself in a basement and write the great American screenplay.

I’d had enough of chasing jobs, chasing girls, chasing dreams, chasing life. Something had to change. My last plan was to figure out a way to start making my own movies and let everything else go.

My former roommate in Prague, Andy, had told me before he left that he had a brother who worked in film sales and distribution. That previous winter, I tracked Andy down and asked him for an introduction. I was looking for any door that would take me out of my current world and into where I wanted to be.

To my surprise, his brother, Nick, was on the way, from the US, to the Berlinale within the next few weeks. I was one country away, so I asked him to meet. A little more effort and I found someone in Berlin I could stay with. With a floor to sleep on, it was now a 5 hours trip for a conversation that may or may not last twenty minutes.

I was on my way back to my family for a wedding, and then anything could happen. Maybe I’d come back to Europe, maybe I’d move to LA, maybe I’d lock myself in a basement and write the great American screenplay.

I’d had enough of chasing jobs, chasing girls, chasing dreams, chasing life. Something had to change. My last plan was to figure out a way to start making my own movies and let everything else go.

My former roommate in Prague, Andy, had told me before he left that he had a brother who worked in film sales and distribution. That previous winter, I tracked Andy down and asked him for an introduction. I was looking for any door that would take me out of my current world and into where I wanted to be.

To my surprise, his brother, Nick, was on the way, from the US, to the Berlinale within the next few weeks. I was one country away, so I asked him to meet. A little more effort and I found someone in Berlin I could stay with. With a floor to sleep on, it was now a 5 hours trip for a conversation that may or may not last twenty minutes.

We sat outside a cinema, with only a short time between screenings, and I absorbed as much advice as I could about a side of filmmaking I knew very little about. I knew how to make a movie, but that’s the easy part. It’s not complete until the audience is found watching it, and there’s a whole side of the industry dedicated to making that happen.

Armed with this knowledge, three months later I was on my way to Cannes, in the south of France, with a short trailer for a screenplay I’d written, and months of sending emails to anyone and everyone who would take a meeting with me.

Armed with this knowledge, three months later I was on my way to Cannes, in the south of France, with a short trailer for a screenplay I’d written, and months of sending emails to anyone and everyone who would take a meeting with me.

Cannes is a glamourous place. But under that golden coat is a belly of hungry filmmakers slithering along the croisette with their unseen films, weighed down by the pressure of the celebrated, they are suddenly shell shocked and rendered invisible by the bloody ocean of everyone else’s films in the market, all screaming “me, me, me.” And there is a division between those films and the films in the competition, walled off by the long line of limousines and the jammed pack crowd outside, as they sit, waiting for hours, with ladders, all for a chance to climb up above the rest of the mob, for one brief moment to take a photo of the stars on the way to the premiere of their films - the films that made it.

One walk through the film market and you can see at least 5 film posters of guys holding holding guns, and another 5 posters of zombies, all probably made by filmmakers who think they did something original, revealing all you need to know about which films no one will remember. In fact, it didn’t matter. I had long ago made a list of the 5 films I wanted to make in my lifetime, and none of them featured a zombie.

But through a handful of scrappy meetings (compared to the hundreds of emails I sent), I learned an enormous amount about the realities of the film market. It was always a recon mission, complete with staying on strangers’ couches, hitchhiking along the Cote d’Azure, and even crashing in a French friend’s car one night after getting stuck without a train back to Antibes.

But through a handful of scrappy meetings (compared to the hundreds of emails I sent), I learned an enormous amount about the realities of the film market. It was always a recon mission, complete with staying on strangers’ couches, hitchhiking along the Cote d’Azure, and even crashing in a French friend’s car one night after getting stuck without a train back to Antibes.

My last day there I had a final meeting with a Hollywood agent. As I went to meet him at our chosen rendezvous, I found him sitting next to someone. The person turned to greet me, and it was Nick, the brother of my former roommate. My surprise of finding him here was only outweighed by the surprise of the agent when he asked “How do you two know each other?” and I answered: “His brother was my roommate in Prague.”

This is, of course, the short, and perhaps more seemingly interesting answer. The less glamorous, but more honest answer is: “I traveled 5 hours to introduce myself simply because my roommate told me he had a brother in film distribution.“ The answer I offered gave the meeting a little extra magic. But the fact was, only now, here under the sunny French Riveria, did it sound so serendipitous. Without that initial contact that winter, I would have never known the person I would have said "hello" to was the very brother my roommate once talked about over beers. This is the reward of effort: Luck.

This is, of course, the short, and perhaps more seemingly interesting answer. The less glamorous, but more honest answer is: “I traveled 5 hours to introduce myself simply because my roommate told me he had a brother in film distribution.“ The answer I offered gave the meeting a little extra magic. But the fact was, only now, here under the sunny French Riveria, did it sound so serendipitous. Without that initial contact that winter, I would have never known the person I would have said "hello" to was the very brother my roommate once talked about over beers. This is the reward of effort: Luck.

“I only knew one film executive when I wrote Sex, Lies, and Videotape. I got lucky. It was easier for me then than it will be now for you.” – Soderberg.

I didn’t know any film executives, but I knew the brother of one. From there, he gave me advice, told me which companies might be interested in my project, and he helped me do exactly what I had set out to do – find the door into where I wanted to be. As they say: Take a leap, and the net will appear.

I was willing to hop on a train and sleep on a stranger’s floor for a twenty minute conversation, and later hitchhike across the Cote D’azur with a backpack filled to the brim of 9 years in Europe, and sleep on the sofas of kind and generous strangers. All of this for the sake of affirming a commitment to learn what I was required to know, if I was going to get where I was required to be.

I was willing to hop on a train and sleep on a stranger’s floor for a twenty minute conversation, and later hitchhike across the Cote D’azur with a backpack filled to the brim of 9 years in Europe, and sleep on the sofas of kind and generous strangers. All of this for the sake of affirming a commitment to learn what I was required to know, if I was going to get where I was required to be.

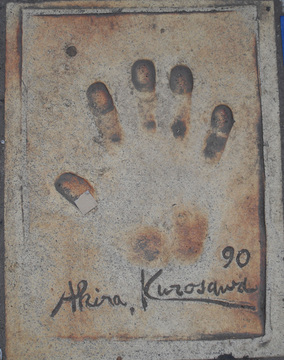

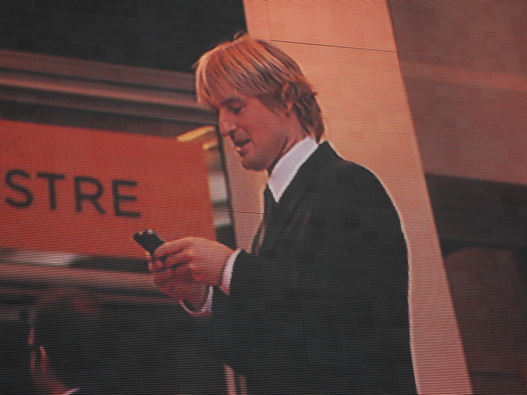

And I still recall standing on the bottom of the red carpet and watching Deniro and Kustarica walk inside the cinema to be celebrated for their own work. And I watched Owen Wilson turn to take a quick snapshot, from his phone, of the crowd gathered on the croisette, before he disappeared inside for the premiere. I later told my mom that in that moment, I’d set a new goal: “One day, I’m going to take a photo like that.” It wasn’t the desire to be photographed or even to be celebrated: but to stand on the mountain of my own hard work, and take a photo of the view.

Epilogue.

“Don’t screw up, or it’s over.”

Steven Soderbergh’s words rang deep then, and they still do now.

But I have screwed up. A lot. I was willing to screw up. I was willing to not know. I was willing to fail. But I also had success. I also took chances not everyone would take. I dared to go. Always. And my life has been remarkable because of that willingness. Not only was I willing to take the chance, I looked for chances, and I followed through with all of them, precisely because I was willing to screw up, I was willing to take the hits, and I refused to believe it would be over, even if it was measured by anyone else to be a failure.

It would only be over if I decided to give up and become a painter. But that would be my choice, not the result of my mistakes.

So, for now, I’m still making my movie.

In retrospect, I think, instead, Mr. Soderbergh’s advice says more about a filmmaker who was also formerly a no-hitter baseball pitcher: Be precise and be smart, because a champion makes every chance count. You might be willing to make the mistakes, but you cannot afford them:

So, if you only know one film executive, write a screenplay called Sex, Lies, and Videotape – and send it to that one person. Do the reconnaissance, sleep on the floors, take the 5 hour trip, learn how to throw the perfect curve ball, make it important to know how to throw the strike. Know the batter you face, so you aren’t the shell shocked filmmaker who wonders why his zombie movie didn’t sell.

Last time I checked, it’s not over for Steven Soderbergh either. He is still making movies.

The Journey Continues

TG

Tyler Gooden is making a film inspired by the legendary true story of FC Start.

If you like stories like these, please follow on Twitter, or Linkedin for weekly posts. For a deeper look into the making of TheFCStartMovie.com, please send an email and receive our monthly behind the scenes updates.

“Don’t screw up, or it’s over.”

Steven Soderbergh’s words rang deep then, and they still do now.

But I have screwed up. A lot. I was willing to screw up. I was willing to not know. I was willing to fail. But I also had success. I also took chances not everyone would take. I dared to go. Always. And my life has been remarkable because of that willingness. Not only was I willing to take the chance, I looked for chances, and I followed through with all of them, precisely because I was willing to screw up, I was willing to take the hits, and I refused to believe it would be over, even if it was measured by anyone else to be a failure.

It would only be over if I decided to give up and become a painter. But that would be my choice, not the result of my mistakes.

So, for now, I’m still making my movie.

In retrospect, I think, instead, Mr. Soderbergh’s advice says more about a filmmaker who was also formerly a no-hitter baseball pitcher: Be precise and be smart, because a champion makes every chance count. You might be willing to make the mistakes, but you cannot afford them:

So, if you only know one film executive, write a screenplay called Sex, Lies, and Videotape – and send it to that one person. Do the reconnaissance, sleep on the floors, take the 5 hour trip, learn how to throw the perfect curve ball, make it important to know how to throw the strike. Know the batter you face, so you aren’t the shell shocked filmmaker who wonders why his zombie movie didn’t sell.

Last time I checked, it’s not over for Steven Soderbergh either. He is still making movies.

The Journey Continues

TG

Tyler Gooden is making a film inspired by the legendary true story of FC Start.

If you like stories like these, please follow on Twitter, or Linkedin for weekly posts. For a deeper look into the making of TheFCStartMovie.com, please send an email and receive our monthly behind the scenes updates.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed